Special education is an overly convoluted topic with the potential to torpedo a politician’s (or policymaker’s) career. As a result, most public figures and organizations give the subject a wide berth. Which is unfortunate, because the very reason for that convolution is what requires action: Special education is broken. It’s a broken solution to an important problem few are willing to speak publicly about. And even fewer are willing to invest the political capital necessary to make more than surface-level changes to the laws that protect our neediest children. No amount of retooling will fix the fundamental flaws of this system — we need an entirely different model.

|

UPDATED

Special education is an overly convoluted topic with the potential to torpedo a politician’s (or policymaker’s) career. As a result, most public figures and organizations give the subject a wide berth. Which is unfortunate, because the very reason for that convolution is what requires action: Special education is broken. It’s a broken solution to an important problem few are willing to speak publicly about. And even fewer are willing to invest the political capital necessary to make more than surface-level changes to the laws that protect our neediest children. No amount of retooling will fix the fundamental flaws of this system — we need an entirely different model.

12 Comments

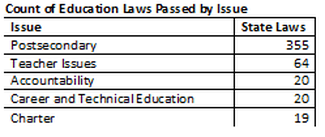

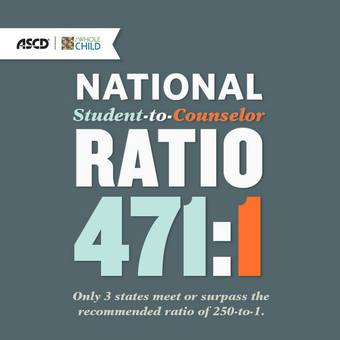

While Congress has spent much of its time gridlocked, state legislatures moved forward with a host of education issues this session — everything from teacher accountability to community college aid. They passed hundreds of bills before ending their lawmaking sessions in early July. Could all of this state action signify some eventual movement in Congress? Using data from Congress and the National Conference of State Legislatures, I found that state legislators have enacted more than 600 bills this legislative session. To better understand these changes, I also calculated the sum of education laws by NCSL education policy topics, which you can see below. (It’s important to note that not all laws create equal levels of change. For example, it’s possible for one law to change the name of a gymnasium and another to create a new teacher evaluation system.) This approach allows for a view into nationwide trends among states, but it doesn’t explain whether these were small or large changes in 2014.  In total, 44 states passed 624 laws relating to education, including primary, secondary, and higher education, this year. Washington (48), Virginia (38), and California (37) passed the greatest number of education laws, and by far, postsecondary education issues dominated legislative action. Some of the new laws provide more scholarship opportunities, make it easier to take classes online, and improve affordability at community colleges. It seems that growing concerns over student debt and general anxieties about the health of the economy are also catching the attention of state lawmakers.  Zakiya Smith speaks at Edu-Jobs. (Credit: Connie Souder) Zakiya Smith speaks at Edu-Jobs. (Credit: Connie Souder) When Zakiya Smith started a job at the U.S. Department of Education in 2009, she said it felt like a demotion. She went from having a corner office as the director of government relations on the Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance to a cubicle at the department as a senior policy analyst. There, she spent a lot of her time as an assistant, scheduling and performing administrative duties. But there were perks, Smith explained to education professionals at the twice-yearly YEP-DC Edu-Jobs event focused on career knowledge and advancement. The biggest? She advised Secretary of Education Arne Duncan on higher education policy and, in turn, had a hand in shaping some of the administration's major higher education proposals. That eventually set Smith on a trajectory that brought her to the White House as a senior policy adviser on higher education issues to President Barack Obama. That’s why you shouldn’t be afraid of making lateral moves, said Smith, now the strategy director at the Lumina Foundation and recently named in Forbes' "30 Under 30." "Do your primary job well, whether that be booking travel or scheduling, then people will usually let you add on things that you want to do," she told the education professionals in the room.  Credit: Assoc. for Supervision and Curriculum Development Credit: Assoc. for Supervision and Curriculum Development Discussions about boosting high school and college graduation rates usually focus on standards, assessments, and teacher and leader development. In all this conversation, however, there’s rarely any talk about school counselors. First Lady Michelle Obama thinks that’s a mistake. If we're to reach the president's Northstar goal (to have the highest proportion of college graduates in the world by 2020), Mrs. Obama says schools and states must empower school counselors to help us get there. That’s why school counselors are a part of her Reach Higher Initiative, she told attendees at the American School Counselor Association (ASCA) conference earlier this month. In 2010, right after Toyota recalled 8 million cars and lost $2 billion in sales due to several fatal car malfunctions, imagine if executives had responded by tripling the price of all of their vehicles. Knowing that consumers associate cost with quality, company leaders may have theorized that tripling the price would help boost confidence in their product.

Would there be a Toyota today? According to Amanda Ripley (of Smartest Kids in the World fame), this is how we should fix teaching.  Credit: NYU Local Credit: NYU Local The U.S. Department of Education recently gave a firm push to colleges and universities to get tough about sexual assaults on campus. Several have come under scrutiny in the last year for failing to address accusations of sexual assault, while some have responded by implementing strict policies that automatically expel guilty offenders. But policies alone won’t fix this problem. Punishments must be coupled with education and awareness programs that empower victims and clarify definitions around rape, so assaults are reported more frequently and campuses address them more openly.  Alison Elissa Cardy (Credit: Connie Souder) Alison Elissa Cardy (Credit: Connie Souder) There was once a lawyer, fresh out of law school, who anticipated he’d make $68,000 in his first job. He was prepared to settle for this sum without a second thought. Law profession and numbers aside, might this sound like your first job? Luckily, for him, his story doesn’t end there. His professor not only scoffed at the figure, but he pushed the lawyer to ask for $80,000. After researching entry-level earnings for someone like him in his city, he found his professor was right: Some of his colleagues were making as much as $85,000. When it came time to discuss figures with his new employer, he used his salary research and qualifications to bargain for more. And he got it: $78,000 — less than the figure his professor threw out, but much higher than he initially would have taken. This is called bracketing, says Alison Elissa Cardy, a Washington, D.C.,-based career coach. It’s when two parties, an employer and applicant, meet in the middle of a suggested salary range. She shared this true story at a salary negotiation workshop hosted by YEP-DC last week to demonstrate the power behind negotiation skills in maximizing one’s earning potential. To reach the higher end of a salary range, Cardy offered the following suggestions: |

aboutYEP-DC is a nonpartisan group of education professionals who work in research, policy, and practice – and even outside of education. The views expressed here are only those of the attributed author, not YEP-DC. This blog aims to provide a forum for our group’s varied opinions. It also serves as an opportunity for many more professionals in DC and beyond to participate in the ongoing education conversation. We hope you chime in, but we ask that you do so in a considerate, respectful manner. We reserve the right to modify or delete any content or comments. For any more information or for an opportunity to blog, contact us via one of the methods below. BloggersMONICA GRAY is co-founder & president of DreamWakers, an edtech nonprofit. She writes on education innovation and poverty. Archives

May 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed