Education policymakers are rarely faced with such clarity of failure. But I often think of this story when leaders talk about new initiatives or recommendations, because it provides such a stark example of policy backfiring. (I studied and worked in international development before moving to domestic education.) There was a common belief among development “experts” at the time that governments were too involved in their economies and in service provision, and that introducing market forces would improve the system. There are many education leaders today who say the same thing, and it’s this thought process that underlies the premise of charter schools. In urban areas, with more infrastructure, money, and greater population densities, it’s a solid premise with a lot of potential. But rural charters are a bad idea for many of the same reasons “market liberalization” was a disaster in southern Africa.

|

In 2002, the nation of Malawi had one of the worst famines in living memory—more than 50,000 people died because of hunger and hunger-related causes. But even that number understates the devastation. Many families clung to survival only by selling all of their possessions, land, and livestock, leaving them no livelihood. Malnourished children contracted debilitating illnesses like kwashiorkor, decreasing their resilience and likelihood of surviving future hardship. Communities were broken by distrust, children sent away from their families, and countless other tragedies occurred that most of us can only imagine. Floods were the natural cause, but government policies were the true disaster.

Education policymakers are rarely faced with such clarity of failure. But I often think of this story when leaders talk about new initiatives or recommendations, because it provides such a stark example of policy backfiring. (I studied and worked in international development before moving to domestic education.) There was a common belief among development “experts” at the time that governments were too involved in their economies and in service provision, and that introducing market forces would improve the system. There are many education leaders today who say the same thing, and it’s this thought process that underlies the premise of charter schools. In urban areas, with more infrastructure, money, and greater population densities, it’s a solid premise with a lot of potential. But rural charters are a bad idea for many of the same reasons “market liberalization” was a disaster in southern Africa.

2 Comments

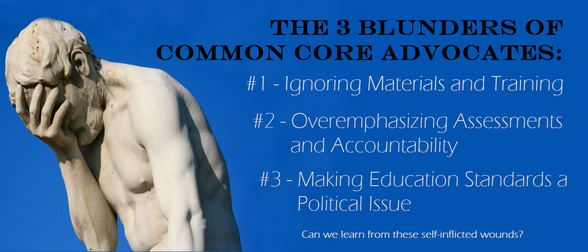

In the end, they came for inBloom with pitchforks. So dramatic! But true. What started as a platform to share student data across states was soon seen as something much more sinister. Parents sued the New York commissioner of education over the state’s involvement with inBloom. Louisiana education activists issued public records requests for the contract and all communications between the state and the Shared Learning Collaborative, inBloom’s predecessor. Superintendents made comments, observers got riled up, and one New York State assemblyman said, well, this. Their primary concern? Student data privacy. When inBloom shut down, it was considered a win for privacy advocates. And while there are legitimate privacy concerns, there’s undeniable value in giving parents, teachers, and students easier access to student achievement data. So what’s the real story? What protections are there for data privacy? How are student data being used?  I went to Brennan McMahon Parton, an expert at Data Quality Campaign (DQC), to get some answers. I also learned about her own data privacy fears—and why a bookshelf in her office is used for heels. Brennan started her career in ed policy in Tennessee, working at the State Collaborative on Reforming Education. More interested in a 50-state perspective, she started looking in D.C. Even though she remembers saying, “I don’t want to work on data! Who wants to work on data?” an opportunity with DQC changed her mind. Now, she works with state leaders and advocates to set the record straight on education data and, in the process, is involved in more active policy environments. “Right now, the conversation focuses so much on federal policy,” she says. “But that’s not where the exciting work is happening.” The beginning of the Common Core story—the creation and deployment of the standards—has come to a close. In Act Two, states will start using new Common Core-aligned exams for accountability purposes. But as two comprehensive polls from Gallup/PDK and Education Next show that the once strong political coalition supporting the standards is falling apart, there are few reasons to have optimism about the political future of the Common Core. For the standards to achieve success, proponents of the Common Core will need to overcome the following three political hurdles:

During the first few weeks of the school year, I’ve noticed teachers in my elementary school reminding students of behavior expectations. I’ve also noticed some students having trouble meeting those expectations. In the past, schools may have been quick to suspend students who are disruptive, but new policies are asking schools to change their practices.

On paper, Common Core is a great idea that—if fully realized—could change education significantly for the better. In reality, implementation has been shoddy, poorly thought out, and lazy. Turning good ideas into effective action is hard work, and a lot of that work didn’t get done, leading us to where we are today (decreasing public support, lawsuits, and an increasingly negative tone in the press). The overarching error has been that Common Core supporters didn’t spend nearly enough time talking to normal people during the initial years of implementation. This has led to underestimating problems that should have been obvious and—disastrously—allowing opponents to frame the issue with little resistance. Common Core is a far cry from failure. More than 40 states, D.C., four territories, and the Department of Defense Education Activity have adopted the standards. It’s not going away anytime soon. But the drop in public support and continued vitriol for fairly innocuous public policy (we’re talking about education standards here!) highlights a number of blunders requiring recognition. And some lessons to be learned.  |

aboutYEP-DC is a nonpartisan group of education professionals who work in research, policy, and practice – and even outside of education. The views expressed here are only those of the attributed author, not YEP-DC. This blog aims to provide a forum for our group’s varied opinions. It also serves as an opportunity for many more professionals in DC and beyond to participate in the ongoing education conversation. We hope you chime in, but we ask that you do so in a considerate, respectful manner. We reserve the right to modify or delete any content or comments. For any more information or for an opportunity to blog, contact us via one of the methods below. BloggersMONICA GRAY is co-founder & president of DreamWakers, an edtech nonprofit. She writes on education innovation and poverty. Archives

May 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed