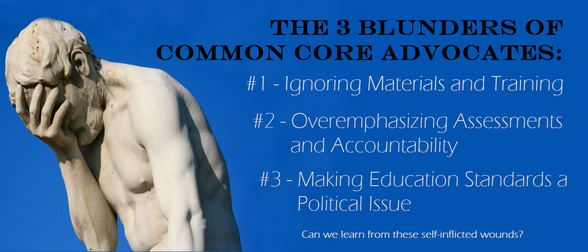

Common Core is a far cry from failure. More than 40 states, D.C., four territories, and the Department of Defense Education Activity have adopted the standards. It’s not going away anytime soon. But the drop in public support and continued vitriol for fairly innocuous public policy (we’re talking about education standards here!) highlights a number of blunders requiring recognition. And some lessons to be learned.

Ultimately, the most important gauge of a policy is how it plays out in the classroom. The quality of classroom materials purporting Common Core alignment, including the notorious math worksheets, has been an embarrassment. I could post links all day to parents highlighting absurd questions from their kids’ homework and tests. While it’s easy for defenders of Common Core to blame teachers or school districts or to point out that bad materials have always existed, that completely misses the point. Much of how English and (especially) math is taught under the standards is new—parents don’t understand the strategies employed, kids certainly don’t, and many teachers don’t. Teachers are navigating a new landscape with no official direction, so they’ve been relying solely on publishers’ claims of alignment. Yet we know that most of what’s being provided is not aligned to Common Core. Teachers are not and never will be Supermen; mere mortals need an opportunity to carry out their jobs. The guidance they require hasn’t been provided with nearly enough consistency.

Lesson #1: Emphasize ease of adoption.

The Common Core website is wonderful, but for whom? What teachers and curriculum coordinators require is a way to easily and readily identify quality instructional materials that are aligned to the standards they must meet. They need textbooks and basal readers that are content-rich and provide the “foundation of knowledge” demanded by the standards. This should have been a top priority from day one. Hoping that quality will trickle down into the classroom because of pressure from high-quality assessments is a typical, conservative approach to management that breaks down in the real world. When implementing (and constructing) policy, it is pivotal that the first consideration be an easy adoption.

Mistake #2: Overemphasizing assessments and accountability.

Without assessments and accountability measures, we have no idea whether the education system is achieving its goals, and less-driven teachers have no performance incentive. But a large number of people including many teachers, loathe standardized tests. It doesn’t matter whether their concerns are valid; what’s important is they are widespread and easily set ablaze. The adoption of new standards and assessments may have happened quietly if Common Core supporters hadn’t needlessly thrown up sparks by strongly harping on accountability up front. It wasn’t until 2014 that a large number of influential supporters started seriously supporting (or considering) the idea of a pause on high-stakes testing, and it wasn’t until teachers were screaming so loudly that everyone took notice of the issue. Outside of the inherent unfairness of instituting a set of accountability measures that a teacher hasn’t been sufficiently trained on or had time to adjust to, it was horrible PR. There is no good reason for teachers (or progressives, more generally) to oppose a set of rigorous, common standards, but support has slipped significantly.

Lesson #2: Public sentiment matters. So does fairness.

This was a self-inflicted wound from an ideological blade. Those interested in improving public education need to do a better job of gauging public sentiment on issues like testing. It’s perplexing, frankly, the way certain organizations and individuals seem to completely ignore the masses when constructing policy or policy recommendations. And in this instance, it only made sense to recommend a pause because it was the right thing to do, given that the assessments were not ready in many cases and in all cases teachers had very little time to adjust to the new expectations. Unions and teachers shouldn’t have had to scream for attention; they should have been granted the concession up front. Even if state or federal constraints didn’t allow for a pause, advocates should have stated their support on the grounds of common sense. Instead, Common Core advocates are now fighting a two-front political war—the only issue in six years that the far left and Tea Party can agree on. Selling a policy to the public, and adjusting it where necessary, isn’t an inconvenience; it’s the job of anyone hoping to shape public policy.

Mistake #3: Making education standards a political issue.

Strongly implying that states should adopt the standards in order to receive a Race to the Top grant (even if “Common Core” wasn’t mentioned explicitly) was a calculated political decision that may have paid off in a different time with a different president. Before President Obama was elected, it would have been difficult to imagine education standards becoming a major battleground in a culture war over federal overreach. But granted those concessions, the behavior of the administration has still been extremely unhelpful. On top of the $350 million budgeted for development of the Common Core assessments, the U.S. Department of Education strongly implied No Child Left Behind waivers would be tied to Common Core adoption (burgeoned by the recent Oklahoma decision), infuriating the Tea Party and others. Today, the largest threat to the future of Common Core is a groundswell of opposition from conservatives, driven by concerns over a federal curriculum and—let’s be honest—a hatred for anything tied to the Obama administration. Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal’s lawsuit, while frivolous on its face, is an attempt to leverage this political inertia for his own ambitions. So naturally the department did the one thing that would bolster his claims and encourage further discontent—they punished a state for dropping Common Core.

Lesson #3: Style points count for nothing; just run out the clock.

The lesson here is simple and well-known to any football fan: A win is a win, and if you’re up by 6 with two minutes left, you don’t throw into heavy coverage. Protect the ball, pick up the first down, and run out the clock. In other words, nearly every state in the country had adopted Common Core; the administration didn’t need to force it (or “college- and career-ready standards”) with NCLB waivers—particularly at a time when the Tea Party was peaking in strength. It was an unnecessary Hail Mary pass thrown directly into the outstretched hands of the opposition defense. Perhaps Arne Duncan and company underestimated the backlash brewing over the standards; perhaps they thought it necessary to decrease the likelihood of the standards’ repeal. Either way, it shouldn’t have happened. Tuck the ball. Take the win. Play another day.

To be fair, there have been slow improvements on all three of the issues laid out. But had there been more public engagement up front and action on these issues early on, Bobby Jindal’s most recent theatrics might have involved his continued support for the standards rather than a populist appeal to destroy them.

Matt Richmond is an education-policy researcher based in the DC area. Reach him via email or Twitter.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed