The GED was developed after WWII to give veterans who dropped out of school to join the war effort a chance to compete in the job market with students who earned their high school diploma. Though created decades ago, the GED assessment has evolved to accommodate changes in K-12 education. in 2014, adaptations were made to align the test with the Common Core State Standards, or CCSS, which made it more difficult.

However, there are concerns about the current iteration of the GED assessment. First, it not provide an adequate measure of workforce skills, which are more valuable to adult students seeking to enter the workforce. And for most of the population the GED serves, expecting them to adhere to CCSS is unrealistic. Most of these students have been out of school for ten or more years. Many of them floated by under the radar while in school, barely picking up the basics, and many have forgotten how to keep up with school work, especially with their additional responsibilities as adults. There is a significant population of adult students who are homeless, who have mental health issues, or who have a history of drug abuse. These students do not have the resources to juggle their hardships with the fact that they essentially have to start all over again as a high school student.

Since the GED overhaul in 2014, the pass rate has dropped, dramatically. More than 401,000 people in the United States earned a GED in 2012, and more than 540,000 earned one in 2013, but in 2014, just over 58,000 passed the test. That’s a 90 percent drop rate.

Secondly, many of the GED changes also place additional burdens on adult educators who must prepare students for the test. Privacy measures make it difficult for the students and their teachers to accurately assess what skills the students still struggle with. For instance, students automatically receive a score for practice tests, but the student is not able to see which questions he or she marked incorrectly. A score could be the result of a few skipped or misunderstood questions, an accidental marking of "C" when the student meant to click "B," or a misspelled answer in a fill-in-the-blank question. Instructors have no way to know, which makes it harder to identify problem areas for students.

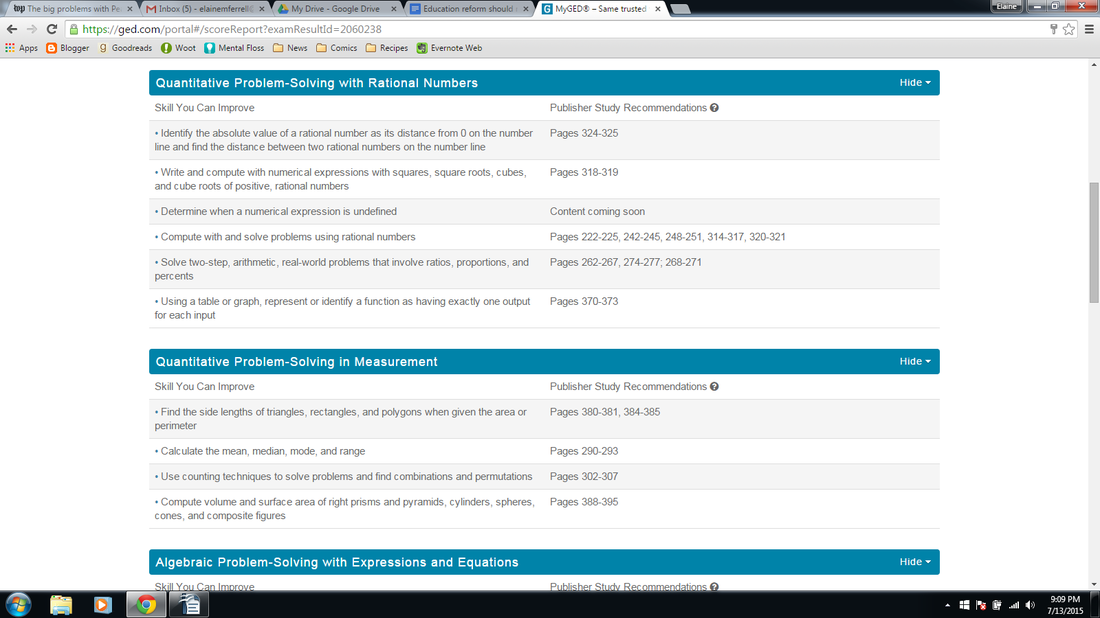

Pearson, the administrator of the GED, provides an analysis of what students can do to improve their scores, but because of the tight privacy surrounding the exam, it is not terribly helpful. Below is an example of what a student might receive after seeing his/her score.

Under the "Skill You Can Improve" section, each "skill" is actually an amalgam of skills (especially regarding math), which makes it difficult to pinpoint exactly what the student struggles with. It could be that students have mastered computing volume but not surface area (or mastered both skills with pyramids but not cylinders), yet these are lumped together. And the Kaplan text book this breakdown recommends has one page of explanation and one page of practice problems per skill—not enough for anyone to master a particular skill.

The breakdown Pearson provides is especially frustrating with the writing section, in which neither the instructor nor the students can see what students wrote, only what their final grades are. As an educator and a student, a grade means nothing to be without the rationale to back it up. Why was the student given a B? How can they get better? It pains me as an educator that I cannot tell them why they received the score they were given. I am constantly baffled by students who are strong writers in my class who end up scoring a zero on the writing section.

Most adult students deserve a second chance, but it is difficult for them to achieve one with the current iteration of the GED. We need to change the difficulty and secrecy surrounding the GED, but first we need to bring this issue to the forefront. There has been some press about it, including media attention about DC’s population of adult learners, but there has not been enough. As it is now, the GED test (and by extension, adult education) is a neglected sector, which must change so that all citizens have a chance at receiving a high school diploma.

Elaine Ferrell, guest blogger, is a GED teacher in D.C. and previously taught high school English. She also co-chairs an all-volunteer group of educators and policymakers that helps develop policies affecting low-income children and adults in D.C. Reach her via email.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed