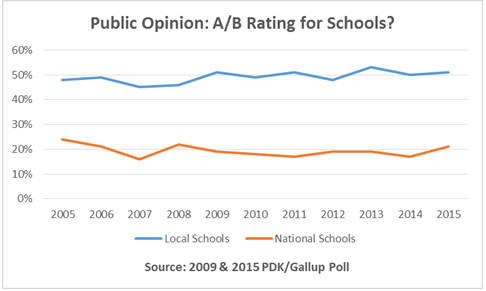

According to the poll, 51 percent of Americans awarded the schools in their community a grade of A or B. That number was even higher – 57 percent – among parents of children in public schools, and the view was consistent across party lines. Only four percent gave their local schools a failing grade.

However, public opinion of schools at the national level was very different. Only 21 percent of people thought America’s schools deserved an A or B grade. Last year that number was 17 percent. And nearly two-thirds of Americans believe that less than half of public school students receive a high-quality education.

And this dichotomous view has persisted over time. According to the survey report, it is “a pattern that has held across 40 years of the PDK/Gallup poll.”

As a result, we are lagging behind at the international level. Every three years, samples of students in various countries participate in the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), which measures the competence of 15-year-olds in reading, mathematics, and science literacy. Among the 34 member nations of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) – generally considered to be the world’s most developed countries – the United States performed at an average or below average level in all three categories. In reading, math, and science, we ranked 17th, 27th, and 20th, respectively. To make matters worse, OECD reports that the United States has had “no significant change in these performances over time.”

So why do Americans consistently have a positive view of their community’s schools? Political scientist Robert Shapiro offered one theory in the PDK/Gallup report: the difference in local and national opinion is based on where people get their information. “Americans form their opinions about their local schools through their own contact with the schools and what their children are saying. What they experience more personally, they tend to have more favorable views about,” Shapiro said. “Nationally, they’re developing their opinions from what they hear on the news, about the problems at schools in general.”

This explanation is evident in other polling as well. For example, people tend to have a very different view of the congressman from their district relative to Congress as a whole. According to Gallup’s most recent polling, Congressional approval sits at 14%, and historically that figure rarely eclipses 20%. However, people’s approval of the representative from their own district is almost always over 45%, and often closer to 60%.

Gallup methodologist Stephanie Kafka, also quoted in the PDK/Gallup report, puts it best: “The further I get from my front door, the more likely I am to become negative.”

This method of forming opinions helps explain why building support for new education initiatives is so difficult. There is often broad agreement on general principles (e.g., raising academic standards and making them comparable across state lines), but the implementation of new programs usually receives lots of backlash because people don’t want to see large-scale changes in their own schools.

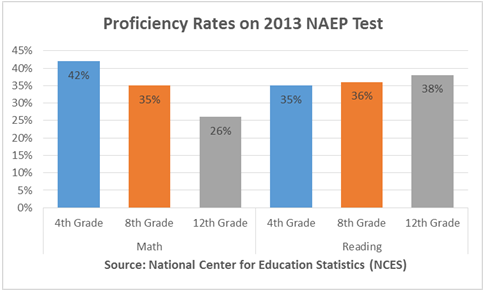

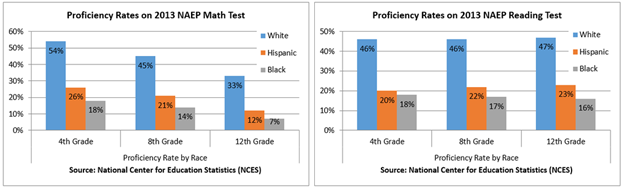

However, not everyone views schools this way. For the first time since the PDK/Gallup poll’s inception in 1969, it measured the grading of local schools among blacks and Hispanics – a significant piece of news in and of itself. Only 23 percent of black people gave their schools an A or B grade. For Hispanics, that number was 31 percent. When compared to the general public, these numbers are much more in line with views of national schools than of local schools. The difference between these groups’ opinion and the opinion of the sample as whole are not surprising. The schools that are regarded poorly at the national level – urban, low-income schools with high populations of minority students – are exactly the schools that blacks and Hispanics are most likely to attend. And those groups’ concerns with their local schools are wholly justified. As the charts below demonstrate, there is a dramatic gap in achievement between black and Hispanic students and their white peers:

Phillip Burgoyne-Allen is a policy analyst at Bellwether Education Partners. Reach him via email or Twitter.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed