Credit: Scott Goldstein

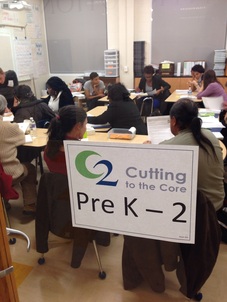

Credit: Scott Goldstein And that lesson is more important than ever, as states roll out assessments tied to the Common Core State Standards that will ask students to choose not just the right answer — questions can have more than one correct response — but the best answer. Earlier this month, teachers from across D.C. gathered to strategize how their instruction can facilitate this change in thinking. (They were meeting for the final “Cutting to the Core” professional development session of the fall semester, an event sponsored by Teach Plus D.C.) How do we shift the mindset of our students from seeking the one easy, right answer to searching to unearth several right answers? To tackle this difficult task, I co-facilitated a session that explored best practices in four key areas: “teacher talk,” student feedback, assessment formation, and “student talk.”

Secondly, we can shift the mindset of our students through the feedback we give them on a daily basis. Consistent, positive reinforcement with students who think aloud and build on the ideas of their classmates can multiply that behavior. Our feedback must be specific and meaningful enough that students know what to do with it: not a pat on the back or a slap on the wrist, but a constructive push forward. Instead of viewing peer correction as a means to save teachers from the burdens of grading, we should see it as an essential tool for student learning. If our assessments are strong, allotting sufficient time and structured activities for students to understand why, and how, their peers arrived at different answers could focus their attention on the process and not simply the result.

Third, we can form assessments that prompt students to think more critically. This means more than a simple shift toward more open-ended questions; even multiple-choice questions should be thought-provoking. Questions should ask students to prioritize, justify (or negate), and provide evidence. Additionally, teachers in my group said that each standard should have multiple questions to assess it, and those questions should become increasingly more rigorous so we can best identify where students stumble. Restructuring our assessments to a more standards-based approach helps both students and teachers plan better for more effective future study.

The final piece of the puzzle is the most difficult to accomplish and the one, teachers in our group acknowledged, we have the least control over: a shift in student discussion with each other. There are more direct methods of encouraging students to routinely think more critically, like posting sentence starters, key questions, academic vocabulary, and modeling phrases. But teachers can also create structured class time to debate, discuss, and develop student thinking, using prompts like “What do you mean when you say …?”

Sometimes students are so concerned about getting the answer right that they don’t take the time to think through all of the complexities and nuances of potential responses. Shifting the mindset of our students toward this kind of critical thinking is essential because it’s there that the real learning takes place.

If you are a teacher in D.C. and interested in further Common Core professional development, join Teach Plus in our spring semester of “Cutting to the Core.” More information can be found here.

Scott Goldstein is a social studies and ESL teacher at a D.C. public charter school. He can be reached via email or Twitter.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed