|

When disasters like Typhoon Haiyan (known in the Philippines as “Yolanda") strike, it is not only buildings that are destroyed; communities are also devastated. Tacloban City, one of the worst hit areas, is home to 38 public elementary schools and 11 public secondary schools, plus an additional 46 private schools. Students, parents, and teachers are undoubtedly among the 2,300 Filipinos who lost their lives in the typhoon and the 11 million who have otherwise found themselves affected by the disaster. Research has shown that in the aftermath of disasters, where schools have been destroyed, community links play a vital role in reinstating education and establishing a sense of normality. As public and private schools begin accepting transfer students whose schools have been shattered by Typhoon Haiyan, I take a look at a well-respected, community-driven school improvement programs, the Philippines’ Check My School.

0 Comments

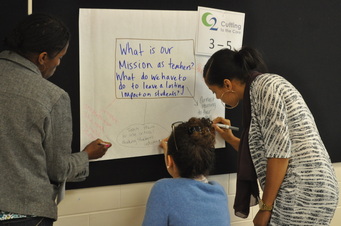

Laura Bohorquez Laura Bohorquez I have had little personal exposure to the plight of undocumented immigrants. The schools where I have worked do not have students who are English-language learners, and most of the families I’ve worked with grew up in the same neighborhoods where they currently live. As a result, I have admittedly missed a very real civil rights issue plaguing our country. My perspective changed when I met Laura Bohorquez and heard her story at The Education Trust’s national conference last month. Laura was born and raised in Mexico City until age four, when her family migrated to rural Washington state. As a result of her undocumented status, she has faced several legal and financial barriers in her pursuit of an education. In spite of these hurdles, Laura was able to complete college in her home state before moving to Chicago for a master’s degree in higher education administration. But many undocumented students don’t end up like Laura. For that reason, and many others, she has become a passionate advocate for undocumented students. Laura has turned her challenges and successes into a platform from which she hopes to motivate others to create change for the undocumented population. Now in D.C., Laura is a coordinator of the DREAM Educational Empowerment Program (DEEP) at United We Dream, where she helps to create networks of educators who are prepared to help their undocumented students succeed. What has your family's experience been as undocumented immigrants? What inspired you to become involved as an advocate for yourself and so many other young people?  Educators talk Common Core at a Teach Plus event. Educators talk Common Core at a Teach Plus event. The new Common Core State Standards (CCSS) represent a federal takeover of school’s curricula constructed without the input of key stakeholders, and they ask teachers to meet impossibly high benchmarks or face immediate dismissal from their jobs. Or that’s what opponents might like you to believe. As a teacher, I understand the resistance to the seemingly never-ending push to adopt new standards, new curricula, and new initiatives before we feel like we’ve even had a shot at the last ones. I understand the worry that we’ll be evaluated on our student’s performance on a new set of dramatically more challenging standards without the time or resources to prepare our students in earnest. But when it comes to the Common Core, it’s time for us to step up. These are the standards we’ve been waiting for.  Courtesy of DeRay McKesson Courtesy of DeRay McKesson In the last six months, I’ve had the opportunity to interview some insightful people within the District of Columbia’s diverse educational circles. We’ve learned about the inner workings of the policy sector from Zakiya Smith and Chad Aldeman, seen how non-profit organization DC SCORES keeps kids healthy and engaged, and experienced the sights and sounds of practitioners at Jefferson Academy and Eastern Senior High School. As a Baltimorean, I know that this same spirit and commitment to education reform runs deep in Charm City. DeRay McKesson, who works for Baltimore City Public Schools, encompasses some of the best qualities of reformers in our area. He’s known for his intense work ethic and positive outlook, and he’s deliberately built a career that allows him to give back to his hometown in a big way. After teaching sixth-grade math in New York City and working for the Harlem Children’s Zone, DeRay returned to his native Baltimore to found a new site for Higher Achievement and serve as a manager for the Baltimore City Teaching Residency (BCTR). From there, DeRay has moved up the district ladder to become the special assistant to the chief human capital officer, helping to oversee all personnel issues for the school system, from labor to licensure, placements to payroll. Here, DeRay shares his career evolution and how his work impacts students and staff districtwide. |

aboutYEP-DC is a nonpartisan group of education professionals who work in research, policy, and practice – and even outside of education. The views expressed here are only those of the attributed author, not YEP-DC. This blog aims to provide a forum for our group’s varied opinions. It also serves as an opportunity for many more professionals in DC and beyond to participate in the ongoing education conversation. We hope you chime in, but we ask that you do so in a considerate, respectful manner. We reserve the right to modify or delete any content or comments. For any more information or for an opportunity to blog, contact us via one of the methods below. BloggersMONICA GRAY is co-founder & president of DreamWakers, an edtech nonprofit. She writes on education innovation and poverty. Archives

May 2017

Categories

All

|

| Search this site |

© Young Education Professionals. All rights reserved.

Logo designed by Aram Designs

Website created using Weebly

Logo designed by Aram Designs

Website created using Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed