Education policymakers are rarely faced with such clarity of failure. But I often think of this story when leaders talk about new initiatives or recommendations, because it provides such a stark example of policy backfiring. (I studied and worked in international development before moving to domestic education.) There was a common belief among development “experts” at the time that governments were too involved in their economies and in service provision, and that introducing market forces would improve the system. There are many education leaders today who say the same thing, and it’s this thought process that underlies the premise of charter schools. In urban areas, with more infrastructure, money, and greater population densities, it’s a solid premise with a lot of potential. But rural charters are a bad idea for many of the same reasons “market liberalization” was a disaster in southern Africa.

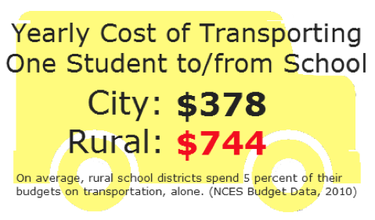

Rural communities, regardless of the country, have a much harder time attracting the kind of resources necessary to benefit from increased “choice.” Often times, a decreased government presence means fewer good choices and a decrease in quality of (affordable) options. In these cases, the market does not improve the situation; it only makes things worse. Consider rural school districts today: Many are faced with small (and shrinking) budgets, have a difficult time attracting and retaining quality staff, are burdened with large transportation costs, and have very little support from community organizations. Their largest challenges are tied to lack of connectedness to resources and economies of scale. Reducing the government’s role and introducing competition to that environment will only exacerbate current problems, just like removing the anchor of government facilities in Malawi exacerbated the already tenuous food security issues faced by rural communities there.

Given these issues, the only real reason to support rural charters is an idealistic belief in maximizing choice for all, regardless of circumstance. But more bad choices aren’t a victory for anyone. We don’t need another policy debate focused on the occasional success story mixed in with a generally poor-performing sector, which rages on indefinitely because there are no malnourished children crystalizing the policy’s failure. There are enough of those already.

In Malawi, the food-security program badly needed reform, just as the U.S. education system needs to improve. But any proposed solution needs to make sense and improve the system. Charter schools don’t make sense in rural school districts. They will only exacerbate challenges and cause more harm than good.

Matt Richmond is an education-policy researcher based in the DC area. Reach him via email or Twitter.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed