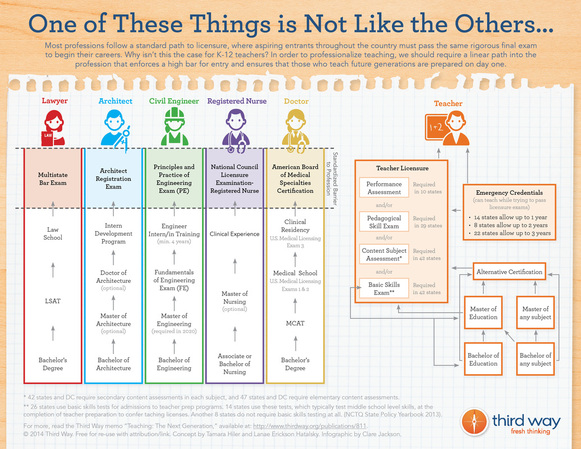

The Third Way report describes the teacher licensure process as a “jumbled mess,” noting that there are more than 600 different licensure tests used across the country. States employ a variety of means to evaluate a potential teacher’s readiness: some simply use multiple-choice exams that test for content and pedagogical knowledge, while others have a much more comprehensive process including “stand-and-deliver” performance assessments. Teachers in some states are required to pass an exam as the final step of licensure, while those in other states must take the exact same exam before entering a teacher preparation program in the first place.

According to the report, the bar for licensure is also set “shockingly low.” States choose the minimum score, or cut score, necessary to pass their licensure exams. Rather than creating a high bar for entry into the teaching profession, the majority of states’ cut scores fall at or below the sixteenth percentile, meaning 84 percent of test-takers pass. That’s a sad statistic, especially when considering that teacher preparation programs “routinely graduate twice as many elementary teachers as are needed each year.”

Problems with Teacher Preparation

Teacher preparation programs have also set a low bar. Today, nearly half of prospective teachers come from the bottom third of their college classes (based on SAT/ACT scores), and that figure is even greater for teachers in high-poverty schools. This differs from some top-performing nations, like Finland, South Korea, and Singapore, all of which draw teaching candidates from at least the top third of the college-going population. The standards for admission into most teacher preparation programs in this country are so low that two-thirds of programs accept over 50 percent of applicants. And the programs themselves lack standardization and consistency between and within states. Even teachers’ unions understand this is a problem. As a recent report from the National Education Association said, “The first step in transforming our profession is to strengthen and maintain strong and uniform standards for preparation and admission.”

In order to ensure that the nation’s teachers are highly qualified, low standards for teacher preparation and licensure need to be addressed. The Department of Education has made an effort to do so with their recent proposal for teacher preparation regulations, which would require states to measure certain program outcomes, such as job placement and retention, the preparedness of their graduates, and their graduates’ performance in the classroom (based on student achievement). Using this data, states would rate their programs using at least four levels: low-performing, at-risk, effective, and exceptional. If a program continuously fails to achieve an effective rating, its newly-admitted candidates would lose eligibility for federal TEACH grants, which provide additional financial assistance to prospective teachers planning to work in high-need schools and fields. Failing programs could also lose state approval and eligibility for federal financial aid. However, the proposed regulations offer states too much flexibility in determining how preparation programs are assigned different rating levels, making federal oversight difficult and interstate comparability nearly impossible.

Possible Solutions

While the Department of Education’s current effort is a step in the right direction, we need a holistic approach that accounts for both preparation and licensure:

- First, teacher preparation programs need to set a high bar for admission, including both candidates’ GPA and performance on standardized tests.

- Second, preparation programs themselves must have comparable and consistent program structures that focus on both pedagogical knowledge and student-teaching experience.

- Third, the federal government must implement strong accountability provisions that impact programs’ eligibility for federal funding. States should have the flexibility to rate their own programs, but the measures and definitions they use to do so must allow for state-to-state comparisons.

- Lastly, teacher licensure requirements need to be rigorous and comparable across state lines so that, no matter where you are, you know that students are being taught by someone who is properly qualified. Enforcing this would require some sort of national-level body, like a committee consisting of state educators and leaders, as is suggested in the Third Way report.

Over the next 10 years, roughly 3 million teachers are expected to enter American classrooms. If we strengthen our systems for preparing and licensing them, we have a real opportunity to improve long-term student achievement across the country. If we don’t, more and more students will have teachers who are underqualified and underprepared. We can’t afford not to act: teachers are too important.

Phillip Burgoyne-Allen is a legislative assistant at an education law firm. Reach him via email or Twitter.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed