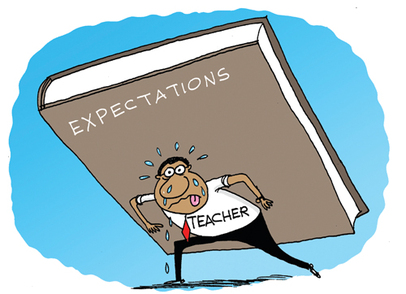

Even the best teachers in D.C. public schools can be observed up to 10 times in an academic year, but educators in neighboring, higher-performing counties in Virginia (Loudon and Fairfax) and Maryland (Montgomery) are evaluated far less frequently.

In Virginia’s Loudoun and Fairfax counties, as well as Maryland’s Montgomery County, tenured teachers are formally observed on a three-year schedule.

In Loudoun County and Montgomery County, teachers are observed every three years. Loudoun and Montgomery also both require three-year and two-year probationary periods, respectively, when teachers are observed more frequently. And in Fairfax County, officials employ a three-year cycle that includes a summative evaluation (which looks at three years collectively) and two formative evaluations (which consider a teacher’s yearly progress).

Without frequent formal evaluations, teachers in these counties have more time to hone their craft and pedagogy without worrying about often-disruptive evaluations.

Additionally, in DCPS, teachers are evaluated on nine standards of practice—such as developing higher-level understanding through effective questioning and providing students multiple ways to move toward mastery. Because of this number of standards, their observed lessons must demonstrate more of their abilities and contain more components than observed lessons in Fairfax County (seven standards), Montgomery (six standards), and Loudoun (five standards).

Additionally, in DCPS, observations are not announced, which can make teachers feel “on edge.” In Montgomery County, at least one of the formal observations must be announced, and in Fairfax, a teacher has the option of requesting a pre-conference before a formal observation, ensuring that in both of these counties, a teacher is always prepared to present his or her best self.

Admittedly, D.C. has challenges that these counties do not. Based on the U.S. Census, Loudoun, Fairfax, and Montgomery counties have a higher number of residents with bachelor’s degrees, a higher median household income (almost double that of D.C.), and much lower poverty rates. That means D.C. teachers need that much more support: more mentoring from experienced teachers, more access to technology, more resources—not more frequent and highly stressful evaluations.

D.C. could learn a thing or two from its neighbors.

Amara Pinnock is an elementary school teacher in DC. Reach her via email or Twitter.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed