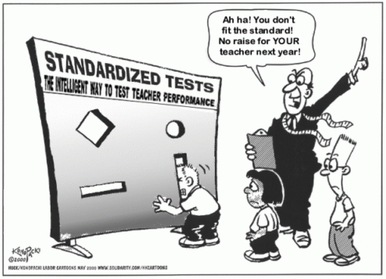

Value-added models attempt to estimate the effects individual teachers and schools have on student achievement, while accounting for differences in student background. This estimation is usually done through standardized testing.

Education experts have long suggested that teacher evaluations should not include a value-added component, as they have the potential to undermine student achievement in the long run because of the actions teachers may take because of increased pressure. For example, teachers may resort to “teaching to the test,” or in other ways, superficially incentivize achievement, so students’ scores look good during evaluation time. Studies have shown that teachers account for only 1 percent to 14 percent of the variability in student test scores, whether positive or negative. There are a variety of factors that affect student performance that are completely outside of a teacher’s control, such as hunger and nutrition, availability of instructional technology, fear and safety at school, frequent changing of schools (by students), and—the list goes on.

So how can we evaluate teachers instead?

Ideally, a teacher should be evaluated on what is within his or her control and the quality of the efforts or inputs he or she makes to increase student mastery of learning objectives. We cannot expect teachers to be the sole proprietors of student achievement, when there are societal issues, like massive poverty and social inequality, facing our students every day.

Instead, teachers (and frankly, schools) should be evaluated on the inputs they utilize to increase student learning. Are they capitalizing on available opportunities to improve their students’ achievement? Are they able to use data effectively to advance their students’ learning? Can a teacher create and teach high-quality units, evaluate her students, see where the students lack mastery, and re-teach and re-test as necessary? And if not, mentors and administrators should provide support as needed.

Similarly, does a teacher know her content? And can she present her content in a way that is accessible to the intellectual capacity of her students?

Finally, teachers should be evaluated by people they know and are comfortable with, rather than an outside expert they have never met prior to the evaluation. Evaluators should be principals, vice principals, and master teachers of the school they work for and have a mentor-type relationship with the teachers they evaluate. Evaluations by those who are familiar with one’s teaching can have a more meaningful impact than those done by individuals the teachers are not familiar with. Someone who works with a teacher on a weekly or monthly basis in a school is more privy to the actions that teacher makes to improve her pedagogy and practice than an outside evaluator would be. As a result, this familiar evaluator would be more invested in the growth of that teacher and be able to give feedback that is directly relevant and applicable, as opposed to an outsider observing something that may have simply been a fluke.

Using a rewards and consequences system for evaluation continues to alienate, and oftentimes, drive away effective educators. As evaluations weigh more heavily in hiring/firing decisions and school-wide accountability models, it is time policy makers and administrators take a deep look at whether value-added models are working—before effective teachers leave the profession.

Amara Pinnock is an elementary school teacher in DC. Reach her via email or Twitter.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed