Credit: Global Education Network

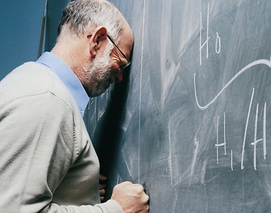

Credit: Global Education Network All of this commotion begs the question: At what point do observations and evaluations become more disruptive than helpful? Do such frequent evaluations give teachers enough time to make appropriate changes to their practice? Or does it just create a more stressful environment for both teachers and students?

In my short time teaching, I have been observed more often than most, in part because I am part of a high-intensity teaching program. I am observed by my coach and sometimes our site director, in addition to my principal and master educator—and then some more from our school’s literacy coach and sometimes from the central office when they decide to visit. When observations occur, which are almost always unannounced, it’s almost impossible to predict how they will go. Teaching in a school with extreme behavior incidences, I am often worried about the behaviors students might exhibit during an observation. This year alone, I have been hit, cursed at, and had things thrown at me by students. Having to worry about egregious student behaviors, on top of a hovering evaluator, can be a rather nerve-wracking experience—especially since having students who are off-task can lower my evaluation score. (I have often heard of teachers bribing their students with treats, food, even parties, in order to get them to behave during evaluations or whenever any guest walks into the room. Others coach their students on how to respond to adults’ questions about their learning.)

But the one thing my teaching program gets right with evaluations is the advanced notice they give. Before I am evaluated by my coach or site director, I have to submit a lesson plan—complete with questioning, differentiation strategies, assessments, manipulatives, and anything else I will need that day. I believe that advanced notice allows me to be able to demonstrate my best and really show off my skills to the evaluator. However, evaluations done by the district are unannounced, and when master educators are in our building, you know it—because all teachers are on edge. With drop-in evaluations, it almost feels like evaluators are looking for reasons to mark you down. They rarely greet the teachers, never smile, and simply sit in a corner and write. My program, on the other hand, is hands-on and evaluators are interacting, assisting, and talking with students.

While D.C.’s IMPACT makes sense to evaluate teachers five times per year (roughly every two months), the district might consider allowing teachers to schedule their observations within a window of five to seven days. In this way, master educators have the opportunity to see all of the teachers at their best. Depending on the time of day or the time of the year for students (near holidays, on a Friday, after lunch, after recess, etc.), a teacher’s performance—and her students’—can vary drastically. And all of those informal visits? Consider making these ones that teachers can volunteer for, if they feel they need the extra help or simply want to know how they are doing before an official evaluation. Or perhaps an administrator can decide a teacher needs the extra support and should sign up for one. In this way, teachers take part more directly in their own self-growth and in their career trajectory.

As a newer teacher who is still learning the ins and outs of effective teaching, the IMPACT model seems more disruptive than beneficial. There are ways as demonstrated by my teaching program, that observations can be more helpful and less punitive. With more autonomy and fewer evaluations, teachers would have the time they need to experiment and make gains, creating a more positive experience overall.

Amara Pinnock is an elementary school teacher in DC. Reach her via email or Twitter.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed