Scandal’s Olivia Pope is the fixer extraordinaire who commands attention whenever she enters a room. Confident in her skills, she has no qualms about voicing her opinions to benefit her clients. Depending on your lens, however, Pope could be an “angry black woman,” whose presence is more “intimidating” than impressive. At least that’s how New York Times writer Alessandra Stanley described Olivia Pope in a much-criticized (really, a lot) article about producer Shonda Rhimes and the expansion of black female leads on television.

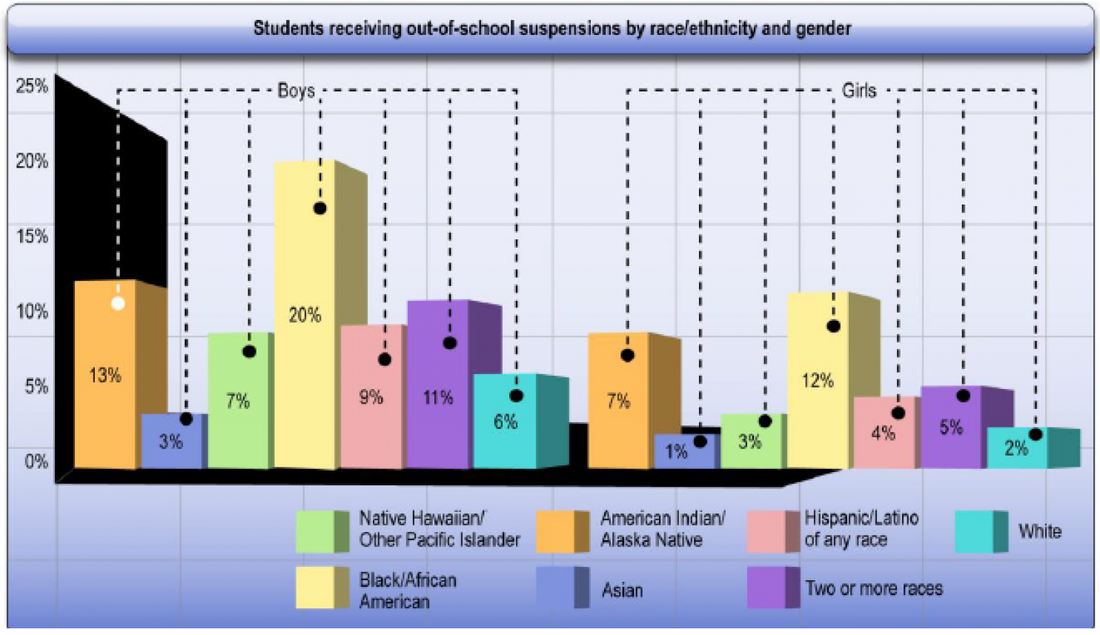

Stereotypes about black women reach far beyond the New York Times and television, trickling down from colleges to elementary schools. The belief that black girls are “angry” and “aggressive” has an adverse impact on their educational experiences, according to a report by NAACP Legal Defense Fund and the National Women’s Law Center. Twelve percent of all African-American girls in prekindergarten through 12th grade receive an out-of-school suspension, which is six times the rate of white girls and more than any other group of girls and several groups of boys. When it comes to achievement, black 12th-grade girls score lower than any other group of girls in reading and math on the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

When educators have negative perceptions about black girls’ social and emotional behavior, whether they are aware of them or not, those perpetuates low expectations that can keep black girls will successful in challenging education environments. The Center for American Progress notes that biased beliefs about a child in elementary school can affect educational outcomes in high school and beyond. What a child’s teacher believes about a student in pre-kindergarten heavily influences that child’s high school grade point average. There is a strong relationship between teacher expectations and college-going outcomes, and when those expectations are tainted by cultural bias and stereotypes, black girls lose out.

It’s critical that educators from all backgrounds raise their awareness regarding the stereotypes they have of black girls. Culturally competent educators have the awareness, knowledge, and skills to work with students from diverse backgrounds. Awareness, however, isn’t limited to what educators know about their students’ backgrounds. As educators, awareness begins by reflecting on our own life experiences and how those experiences can create biases that cloud the lens through which we view our students. We should constantly seek out opportunities to reflect on our beliefs and our practices to ensure our classrooms are promoting equitable outcomes for diverse students.

School districts can support this by providing disaggregated discipline and course selection data to examine the intersection of gender and race. These data would help schools have courageous conversations about why disparities between black girls and other student groups exist, and to set goals to close to eliminate these inequitable outcomes. Though President Barack Obama’s My Brother’s Keeper initiative is focusing on improving outcomes among young men of color, we must focus on black girls as well. The future Olivia Popes and Shonda Rhimes of the world are depending on it.

Connie Ward is an elementary school counselor in Maryland. Reach her via email or Twitter.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed