Credit: cccfs.com

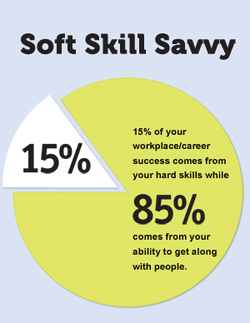

Credit: cccfs.com Knowing that serious career and life preparation requires a commitment to soft skills in our schools, teachers must begin to take the lead by observing, teaching, and assessing soft skills in the classroom.

The first thing teachers can do is take an active role in monitoring, noting, and informing students of their soft skill strengths and weaknesses.

If a student raises his hand after only 10 seconds of trying a new activity, I know I have to step back, not forward. At the TESOL (Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages) International Convention in Portland, Ore., last month, education consultant Laurel Pollard proposed a simple idea for every classroom: a poster that says, “Ask three before me!” The idea has real-world and workplace implications. If an employee misses something at work, he can’t always go directly to the boss. Students need to learn to use every resource at their disposal to acquire the information they need to get the job done. If we can replicate this in the classroom, it will help them establish these habits. Pollard said we should encourage students to make as many mistakes as they can, as long as they don’t make the same ones twice. Learning from mistakes in an explicit way is also key to soft-skill development. Students must be able to step back and analyze their own actions — something we could ask them to do in the context of any classroom, regardless of subject — on a regular basis.

The second way teachers can build soft skills is with more explicit instruction. At our school, I have begun piloting a curriculum this year on Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) skills within my ESL (English as a Second Language) class. SEL skills are, for me, one of the most important focus areas of soft-skill development because soft skills are often put in the context of an individual’s emotional intelligence. The curriculum, which uses the University of Oregon’s Strong Kids books, helps students speak honestly and openly about issues that affect them at school, work, and home. The curriculum focuses on teaching them to understand emotions and to be more thoughtful about appropriate responses. Students learn that emotions, especially ones like anger, are actually helpful forces that can help them make better decisions, if they know how to process them. To be strong collaborators in the workplace, they’ll have to know how to process feelings like resentment, anger, frustration, and impatience. The skills to do this successfully simply don’t come naturally; they are skills that we all learn, and for students who have had extraordinary challenges in their lives, they have too often learned to suppress emotion rather that constructively address it.

Finally, the most important way for teachers to build an emphasis on soft skills is to assess them appropriately — and separately from academic skills. Unfortunately many of the current assessments out there that claim to assess life skills and career readiness simply don’t keep up with the times and aren’t relevant to learners. When assessments ask students to balance a checkbook using a register or interpret a time-clock scenario that uses paper systems that most workplaces replaced years ago, these scenarios simply don’t ring true for students. Until standardized assessments adapt, teachers can and should take it upon themselves to ensure that students possess relevant job skills, are prepared to confront modern workplace scenarios, and have the social and emotional skills they need to form and maintain healthy relationships and positive self-esteem.

Schools must be holistic places. We cannot extricate academics from soft skills, and we cannot view our role as teachers and educators as solely academic in nature. College and career preparation demands an approach that grows the whole student and prepares her to be in charge of her learning and life.

Scott Goldstein is a social studies and ESL teacher at a D.C. public charter school. He can be reached via email or Twitter.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed