To get a job?

Be good citizens?

Because … just because! Stop questioning the obvious!(?)

Getting a job and supporting oneself is probably a minimum — at least to our modern conceptualization of education’s purpose. That’s why we need the Common Core, high-rigor curricula, and standardized tests to make sure that kids can compete in the global theatre!

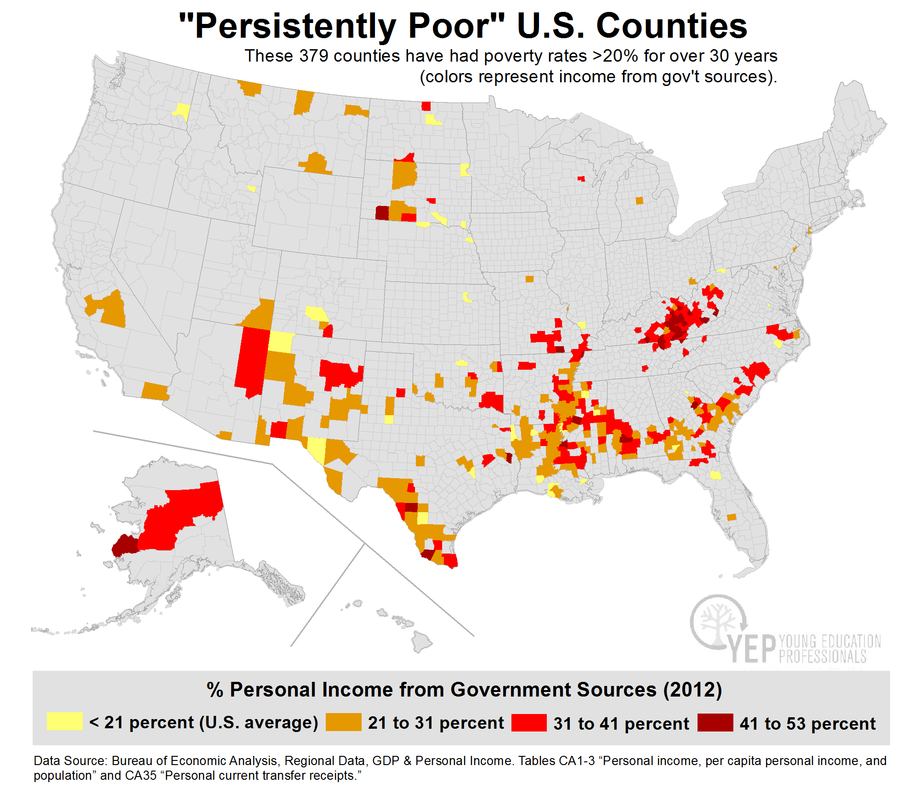

Which is all well and good, but who are we kidding? Are poor, white kids in rural Missouri on the “global stage”? Are Native American students in poverty-ridden South Dakota competing against Indian engineers to build the next iPhone (or even their Foxcomm counterparts)? Fourteen million people in the U.S. don’t even have access to broadband internet (43 percent of households making less than $15,000 a year don’t have ready access to any internet). The global stage is too busy posting gluten-free recipes on Instagram to even notice broad swaths of rural Kentucky.

To understand why schools aren’t the solution, we have to understand the problem. In their prime, the coal, farming, and manufacturing industries were engines of prosperity. As export industries, they fed outside money into the community through their employees’ paychecks, eventually ending up in the pockets of local barbers, doctors, and teachers. Besides this multiplier effect, exports are important because the money earned can then be used to buy stuff from people in other places. Not every poor town used to farm or mine coal, but nearly all of them are lacking the economic foundation provided by industry.

Algebra II, as useful as it is (…), doesn’t make an entrepreneur. Nor is it sufficiently impressive to convince IBM they should build a microprocessor plant in the middle of nowhere. Without outside money feeding back into the regional economy, there will be fewer jobs — with lower wages — across the board. This is why unemployment is so intractable in poor, disconnected areas.

Of course, improving the lives of students doesn’t necessitate healing the community. The goal of experts (who, almost invariably, live in urban areas) focuses much more on the benefits of sending kids away to college. Rural “brain drain” is a double-edged sword, in that it provides kids opportunities they’d never have at home, yet exports the one thing areas can’t afford to lose: skills and talent. But even if we ignore the negative impact and focus on the positive, this isn’t much of a grand plan for students, either.

Any plan to increase opportunity for students needs to focus on building industry first and foremost, because without it the long-term prospects for success are dramatically lower. As the training grounds for future labor, schools need to coordinate with other entities to focus on building skills useful to targeting that root issue. Plans will be regionally specific, but may include career technical education and tax breaks focused on growing wind farm acreage, or entrepreneurship programs which incorporate small startup grants from a local nonprofit, or a land buyback initiative coupled with increased agro-business education. Schools will play an important support role in most any plan — support being the operative word. Many have absurd expectations for education as a magic wand. High-quality schools are a pivotal piece in development, but when there are no jobs, when a community’s culture has developed over multiple generations to expect little opportunity, and there is no credible action to transform the economy, the faculty of Hogwartz wouldn’t have enough magic to change reality.

Some have said that schools use poverty as an excuse for bad teachers, and in many places that’s true. But in the poorest, most disconnected areas of our country, with stalled economies and few prospects for improvement, poverty isn’t an excuse, but a soul-crushing reality. And if so many of us choose to remain focused on single-issue policy and on schools independent of the surrounding world, we will only ensure our own irrelevance and the continued frustration of those who know better.

Matt Richmond is a research analyst for a DC-based think tank. Reach him via email or Twitter.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed