|

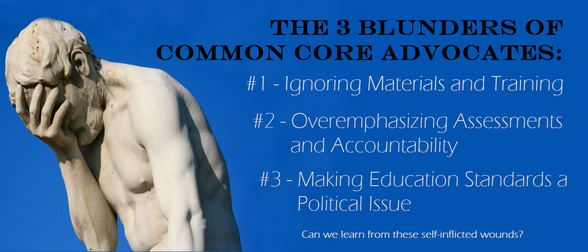

The beginning of the Common Core story—the creation and deployment of the standards—has come to a close. In Act Two, states will start using new Common Core-aligned exams for accountability purposes. But as two comprehensive polls from Gallup/PDK and Education Next show that the once strong political coalition supporting the standards is falling apart, there are few reasons to have optimism about the political future of the Common Core. For the standards to achieve success, proponents of the Common Core will need to overcome the following three political hurdles:

0 Comments

On paper, Common Core is a great idea that—if fully realized—could change education significantly for the better. In reality, implementation has been shoddy, poorly thought out, and lazy. Turning good ideas into effective action is hard work, and a lot of that work didn’t get done, leading us to where we are today (decreasing public support, lawsuits, and an increasingly negative tone in the press). The overarching error has been that Common Core supporters didn’t spend nearly enough time talking to normal people during the initial years of implementation. This has led to underestimating problems that should have been obvious and—disastrously—allowing opponents to frame the issue with little resistance. Common Core is a far cry from failure. More than 40 states, D.C., four territories, and the Department of Defense Education Activity have adopted the standards. It’s not going away anytime soon. But the drop in public support and continued vitriol for fairly innocuous public policy (we’re talking about education standards here!) highlights a number of blunders requiring recognition. And some lessons to be learned.  This fall, schools across the country will administer the new Common Core-aligned assessments. Despite all of the years of toiling and buzz around these new tests, an Education Week analysis finds that only 42 percent of public school students will likely take the test. (Nearly three out of five students are in states that have chosen other tests or haven’t decided yet.) Given the effort by education reformers to promote and advocate for standards, this is unexpectedly low. So what happened?

In March, when Indiana became the first state to drop the Common Core State Standards, supporters of the reform became concerned the political ground was shifting under their feet. The conventional wisdom is that moderates broadly support the reforms while those on the far left and right stand opposed, but the reality is far more complicated and murky. A pair of recent polls offer valuable lessons about the future of the standards:

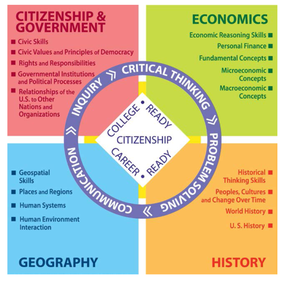

Credit: Minneapolis Public Schools Credit: Minneapolis Public Schools Creating a national curriculum for social students and science is an extraordinary challenge. Both are rich with controversial curriculum debates that strike at a foundational political disagreement over the role of state and the federal government. But it’s a debate worth having, if we’re to create an education system that encourages students to think critically and analytically about the world around them. The Common Core State Standards already drive much of this much-needed and long-overdue change, forcing a depth-over-breadth approach to instruction in reading, writing, and math. But to be meaningful and fully-effective, this approach must extend beyond those skill standards and into content areas like social studies and science. The Common Core State Standards are a reality now for teachers in Maryland and DC, while Virginia is one of six states to omit the standards from their state education approach. YEP-DC asked local educators how the Common Core is playing out in their classroom. Are the standards increasing student understanding or presenting obstacles? What’s changed in pedagogical approach, and how are students are reacting to the shift?

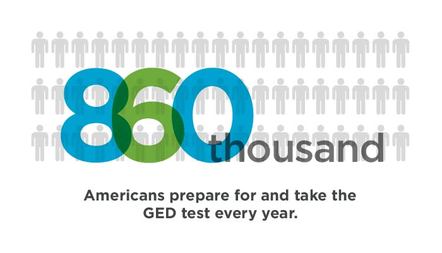

Three teachers gave us a peek into their new Common Core worlds, and here is what they had to say:  Credit: Bill Day Credit: Bill Day It’s probably safe to say that most people know someone with a math phobia. In our increasingly math- and science-driven world, many students (and even teachers and parents!) still struggle to overcome anxieties around basic math skills. With the Common Core State Standards shifting instructional targets and practices, it will be interesting to see how a new approach will affect this all-too-common angst about math. William (Bill) Day, the 2014 D.C. Teacher of the Year, is not only a math teacher, but also a proponent for the Common Core State Standards and a more practical attitude about math education. The Minnesota native started his teaching career in Maine before coming to D.C., where he has been at Two Rivers Public Charter School for the past three years. With wisdom from nine years of teaching, Bill shares his views on the Common Core and the future of math education and also gives us a sense of what’s to come during his Teacher of the Year tenure.  Credit: Scott Goldstein Credit: Scott Goldstein Albert Einstein said that the value of a liberal arts education was “not the learning of facts but the training of the mind to think.” If that’s what we want for our students, a good place to start is training the mind to accept this crucial truth: There isn’t always one right answer. And that lesson is more important than ever, as states roll out assessments tied to the Common Core State Standards that will ask students to choose not just the right answer — questions can have more than one correct response — but the best answer. Earlier this month, teachers from across D.C. gathered to strategize how their instruction can facilitate this change in thinking. (They were meeting for the final “Cutting to the Core” professional development session of the fall semester, an event sponsored by Teach Plus D.C.) How do we shift the mindset of our students from seeking the one easy, right answer to searching to unearth several right answers? To tackle this difficult task, I co-facilitated a session that explored best practices in four key areas: “teacher talk,” student feedback, assessment formation, and “student talk.”  Courtesy of New Readers Press Courtesy of New Readers Press The standards are rising, and so are the stakes. As a teacher in a GED school, the new year brings a new exam, aligned to the Common Core State Standards, that will ask students to go far beyond what the previous test ever asked of them. There is no doubt the transition will be a rocky one as students learn to develop college-level, critical thinking skills. I’m up for the challenge of getting them there, but I’m also aware of the realities: In a school like mine, where we receive students at just about every grade level, we have to consider the effect of telling a 20-year-old student, with a third-grade reading level and a five-year gap in his education, that his next stop is a GED that demands 12th-grade proficiency. I’ve seen it too many times: The student comes in expecting that, just like his more advanced schoolmates, he will study for several months — maybe a year — pass the test, and be on his way to college. A year later, aware of how high a climb he faces, he packs it in and heads for a job market where he faces little chance of upward mobility in the years to come. |

aboutYEP-DC is a nonpartisan group of education professionals who work in research, policy, and practice – and even outside of education. The views expressed here are only those of the attributed author, not YEP-DC. This blog aims to provide a forum for our group’s varied opinions. It also serves as an opportunity for many more professionals in DC and beyond to participate in the ongoing education conversation. We hope you chime in, but we ask that you do so in a considerate, respectful manner. We reserve the right to modify or delete any content or comments. For any more information or for an opportunity to blog, contact us via one of the methods below. BloggersMONICA GRAY is co-founder & president of DreamWakers, an edtech nonprofit. She writes on education innovation and poverty. Archives

May 2017

Categories

All

|

| Search this site |

© Young Education Professionals. All rights reserved.

Logo designed by Aram Designs

Website created using Weebly

Logo designed by Aram Designs

Website created using Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed