Then the consultant mentions that while she was never a teacher, she has personally seen the impact this new innovation has. My attention usually stops there.

It seems that everyone these days has an opinion about how to make teachers and education better. Whether the unwelcome input comes from a politician pushing teachers to disband unions or proposing policies to the detriment of education, or from relatives who claim to know how to quiet a noisy class, everyone has an opinion and claims expertise.

I have always wondered why the people making the major decisions when it comes to education, such as curriculum, student assessment, and the use of test results, are often those with limited—if any—time in the classroom. I believe that if someone chooses to work in the education sector and hopes to have any real impact, he or she should have spent some time in the classroom, as a teacher.

Classroom teachers are privy to all the nuances of working in a school that others would never have considered. Teachers come to understand how broad policies can often mean spending more time at the job, experiencing limited motivation and morale--whether positive or negative--and recognizing that student achievement represents a plethora of other factors other than test scores.

No Child Left Behind, now seen as an enormous failure, is one such example of a law that was created and implemented by people who were never teachers. No Child Left Behind applied a “one-size-fits-all” approach to educational success by only relying on test scores. Every teacher in every classroom has students of all skill levels and is responsible for making sure each student can complete each objective for the entire year. Teachers have to differentiate, create, and apply interventions and accommodations and modifications… yet policymakers simply believed that one test would account for all that learning? Any teacher, whether in a rural, suburban, or urban district, would emphatically say that this approach is asking for failure.

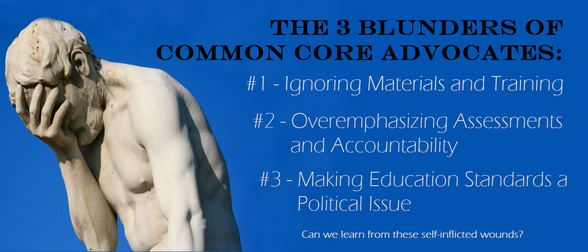

We know that assessments should be differentiated, meaning students should be given options on how to show their mastery of an objective, such as written reports, oral speeches, presentations, cartoons, or something else entirely. We know that some students will need to use class time to work on these final reports because they lack appropriate resources outside of school. We know that it is our job to give students ample opportunity to master an objective and show that mastery, no matter how long it takes. How has recent policy shown that it takes all of this differentiation of assessments into account?

With all this talk around education reform, it seems that Congress is leaving out the key people they need for reform to truly happen—teachers. As I mentioned in a previous post, Congress conducted hearings on the reauthorization of NCLB, and with all of these hearings, only three of those asked to contribute were teachers—three!

When it comes to passing policies and laws that affect our most precious commodities—our students—policymakers need to make more of a concerted effort to include those who work closest with them—teachers. In addition, more teachers need to become more involved with policymakers, by either training to become one, or by aligning themselves with them through fellowships and other such opportunities while remaining in the classroom.

As a teacher, I teach and encourage my students to collaborate well to best meet their objectives and help one another in overcoming challenges, skills outlined in the Common Core. Now, I hope that teachers and policymakers will take a page out of these standards (see Speaking and Listening Standards 1.1, 2.1, 3.1, 4.1...) to collaborate and help one another overcome the biggest challenges facing American education today.

Amara Pinnock is an elementary school teacher in DC. Reach her via email or Twitter.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed